Chapter 31: Performance

This chapter is concerned with performance, that is, the time taken to perform a computation, and how to improve it.There is one golden rule for achieving good performance in a J program. The rule is to try to apply verbs to as much data as possible at any one time. In other words, try to give to a verb arguments which are not scalars but vectors or, in general, arrays, so as to take maximum advantage of the fact that the built-in functions can take array arguments.

The rest of this chapter consists mostly of harping on this single point.

31.1 Measuring the Time Taken

There is a built-in verb 6!:2 . It takes as argument an expression (as a string) and returns the time (in seconds) to execute the expression. For example, given :mat =: ? 256 256 $ 256 NB. a random matrixThe time in seconds to invert the matrix is given by:

6!:2 '%. mat' 0.075273If we time the same expression again, we see:

6!:2 '%. mat' 0.0734835Evidently there is some uncertainty in this measurement. Averaging over several measurements is offered by the dyadic case of 6!:2 . However, for present purposes we will use monadic 6!:2 to give a rough and ready but adequate measurement.

If we intend to compare times for several expressions, it will be convenient to introduce a little utility function:

compare =: (; (6!:2)) @: > "0 NB. compare timings compare '+/ i. 1000' ; '*/ i. 1000' +----------+----------+ |+/ i. 1000|2.14228e_5| +----------+----------+ |*/ i. 1000|8.44842e_6| +----------+----------+

31.2 The Performance Monitor

As well as 6!:2, there is another useful instrument for measuring execution times, called the Performance Monitor. It shows how much time is spent in each line of, say, an explicit verb.Here is an example with a main program and an auxiliary function. We are not interested in what it does, only in how it spends its time doing it..

main =: 3 : 0

m =. ? 10 10 $ 100x NB. random matrix

u =. =/ ~ i. 10 NB. unit matrix

t =. aux m NB. inverted

p =. m +/ . * t

'OK'

)

aux =: 3 : 0

assert. 2 = # $ y NB. check y is square

assert. =/ $ y

%. y

)

We start the monitor:

load 'jpm' start_jpm_ '' 178570and then enter the expression to be analyzed

main 0 NB. expression to be analyzed OKTo view the reports available: firstly , the main function:

showdetail_jpm_ 'main' NB. display measurements Time (seconds) +--------+--------+---+-----------------+ |all |here |rep|main | +--------+--------+---+-----------------+ |0.000004|0.000004|1 |monad | |0.000079|0.000079|1 |[0] m=.?10 10$100| |0.000011|0.000011|1 |[1] u=.=/~i.10 | |0.042640|0.000005|1 |[2] t=.aux m | |0.062151|0.062151|1 |[3] p=.m+/ .*t | |0.000015|0.000015|1 |[4] 'OK' | |0.104900|0.062265|1 |total monad | +--------+--------+---+-----------------+and we may wish to look at the auxiliary function:

showdetail_jpm_ 'aux' Time (seconds) +--------+--------+---+-----------------+ |all |here |rep|aux | +--------+--------+---+-----------------+ |0.000004|0.000004|1 |monad | |0.000004|0.000004|1 |[0] assert. 2=#$y| |0.000010|0.000010|1 |[1] assert. =/$y | |0.042617|0.042617|1 |[2] %.y | |0.042635|0.042635|1 |total monad | +--------+--------+---+-----------------+Evidently, main spends most of its time executing lines 2 and 3 . Notice that the time under "all" of line 2 is near enough equal to the time for line 2 "here", (that is, in main ) plus the time for "total" of aux

31.3 The Golden Rule: Example 1

Here is an example of a function which is clearly intended to take a scalar argument.

collatz =: 3 : 'if. odd y do. 1 + 3 * y else. halve y end.'

odd =: 2 & |

halve =: -:

With a vector agument it gives the wrong results

collatz 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4 4.5So we need to specify the rank to force the argument to be scalar

(collatz "0) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 10 2 16 3 22 4 28This is an opportunity for the Golden Rule, so here is a version designed for a vector argument:

veco =: 3 : 0

c =. odd y

(c * 1+3*y) + (1 - c) * (halve y)

)

The results are the same:

data =: 1 + i. 1e5 (collatz"0 data) -: (veco data) 1Here is a variation. The adverb } is applied to the bit-vector odd y to generate a verb, and the monadic case of this verb meshes together the first and second items of its argument.

meco =: 3 : 0

c =. odd y

(c }) (halve y) ,: (1+3*y)

)

(meco data) -: veco data

1

The vector versions are faster:

compare 'collatz"0 data ' ; 'veco data ' ; 'meco data' +---------------+----------+ |collatz"0 data |0.315611 | +---------------+----------+ |veco data |0.0280563 | +---------------+----------+ |meco data |0.00665947| +---------------+----------+

31.4 Golden Rule Example 2: Conway's "Life"

J. H. Conway's celebrated "Game of Life" needs no introduction. There is a version in J at Rosetta Code, reproduced here:

pad=: 0,0,~0,.0,.~]

life=: (_3 _3 (+/ e. 3+0,4&{)@,;._3 ])@pad

To provide a starting pattern, here is a function rp which generates an r-pentomino

in a y-by-y boolean matrix.

rp =: 3 : '4 4 |. 1 (0 1; 0 2; 1 0; 1 1; 2 1) } (y,y) $ 0' ] M =: rp 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 life M 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0We notice that the life verb contains ;._3 - it computes the count of neighbours of each cell separately, by working on the 3-by-3 neighbourhood of that cell.

By contrast here is a version which computes all the neighbours-counts at once, by shifting the whole plane to align each cell with its neighbours.

sh =: |. !. 0 E =: 0 _1 & sh W =: 0 1 & sh N =: 1 & sh S =: _1 & sh NS =: N + S EW =: E + W NeCo =: NS + (+ NS) @: EW NB. neighbour-count evol =: ((3 = ]) +. ([ *. 2 = ])) NeCoThe last line expresses the condition that (neighbour-count is 3) or ("alive" and count is 2). The shifting method evol, and the Rosetta method life give the same result

(life M) -: (evol M) 1However, the shifting method is faster:

G =: rp 200 NB. a 200-by-200 grid

e3 =: 'r3 =: life ^: 100 G NB. 100 iterations, Rosetta'

e4 =: 'r4 =: evol ^: 100 G NB. 100 iterations, shifting'

compare e3;e4

+------------------------------------------------+-------+

|r3 =: life ^: 100 G NB. 100 iterations, Rosetta |9.66706|

+------------------------------------------------+-------+

|r4 =: evol ^: 100 G NB. 100 iterations, shifting|0.24398|

+------------------------------------------------+-------+

Checking for correctness again:

r3 -: r4 1

31.5 Golden Rule Example 3: Join of Relations

31.5.1 Preliminaries

Recall from Chapter 18 the author-title and title-subject relations. We will need test-data in the form of these relations in various sizes. It is useful to define a verb to generate test-data from random integers. (Integers are adequate as substitutes for symbols for present purposes.) The argument y is the number of different titles required.

maketestdata =: 3 : 0

T =. i. y NB. titles domain

A =. i. <. 4 * y % 5 NB. authors domain

S =. i. <. y % 2 NB. subjects domain

AT =. (?. (#T) $ # A) ,. (?. (#T) $ #T) NB. AT relation

TS =. (?. (#T) $ _1+# T) ,. (?. (#T) $ #S) NB. TS relation

AT;TS

)

'AT1 TS1' =: maketestdata 12 NB. small test-data

'AT2 TS2' =: maketestdata 1000 NB. medium

'AT3 TS3' =: maketestdata 10000 NB. large

31.5.2 First Method

Recall also from Chapter 18 a verb for the join of relations, which we will take as a starting-point for further comparisons. We can call this the "first method".

VPAIR =: 2 : 0

:

z =. 0 0 $ ''

for_at. x do. z=.z , |: v (#~"1 u) |: at , "1 y end.

~. z

)

first =: (1&{ = 2&{) VPAIR (0 3 & {)

| AT1 | TS1 | AT1 first TS1 |

| 0 6 2 8 1 4 3 6 2 5 1 4 4 10 1 4 8 8 7 7 3 9 5 8 |

0 0 3 2 7 4 0 0 0 5 4 4 1 4 10 4 8 2 4 1 1 3 5 2 |

2 2 1 4 1 1 4 4 8 2 7 4 5 2 |

This shows that, for example, if author 5 wrote title 8, and title 8 is about subject 2, then author 5 wrote about subject 2.

31.5.3 Second Method: Boolean Matrix

Here is another method. It computes a boolean matrix of equality on the titles. Row i column j is true where the title in i{AT equals the title in j{TS . The authors and titles are recovered by converting the boolean matrix to sparse representation, then taking its index-matrix.

second =: 4 : 0

'a t' =. |: x

'tt s' =. |: y

bm =. t =/ tt NB. boolean matrix of matches

sm =. $. bm NB. convert to sparse

im =: 4 $. sm NB. index-matrix

'i j' =. |: im

(i { a),. (j { s)

)

Now to check the second method for correctness, that is,

giving the same results

as the first. We don't care about ordering, and we don't care about

repetitions, so

let us say that two relations are the same

iff their sorted nubs match.

same =: 4 : '(~. x /: x) -: (~. y /: y) ' (AT2 second TS2) same (AT2 first TS2) 1Now for some times

t1 =: 6!:2 'AT2 first TS2' t2 =: 6!:2 'AT2 second AT2' t3 =: 6!:2 'AT3 first TS3' t4 =: 6!:2 'AT3 second TS3' 3 3 $ ' '; (#AT2) ; (#AT3) ; 'first' ; t1; t3 ; 'second' ; t2; t4 +------+----------+--------+ | |1000 |10000 | +------+----------+--------+ |first |0.0356744 |7.916 | +------+----------+--------+ |second|0.00337303|0.321806| +------+----------+--------+We see that the advantage of the second method is reduced at the larger size, and we can guess this is because the time to compute the boolean matrix is quadratic in the size. We can use the performance monitor to see where the time goes.

require 'jpm'

start_jpm_ ''

178570

z =: AT3 second TS3

showdetail_jpm_ 'second' NB. display measurements

Time (seconds)

+--------+--------+---+----------------+

|all |here |rep|second |

+--------+--------+---+----------------+

|0.000007|0.000007|1 |dyad |

|0.000329|0.000329|1 |[0] 'a t'=.|:x |

|0.000208|0.000208|1 |[1] 'tt s'=.|:y |

|0.177003|0.177003|1 |[2] bm=.t=/tt |

|0.131638|0.131638|1 |[3] sm=.$.bm |

|0.000009|0.000009|1 |[4] im=:4$.sm |

|0.000160|0.000160|1 |[5] 'i j'=.|:im |

|0.017383|0.017383|1 |[6] (i{a),.(j{s)|

|0.326736|0.326736|1 |total dyad |

+--------+--------+---+----------------+

Evidently much of the time went into computing the boolean matrix at line 2.

Can we do better than this?

31.5.4 Third method: boolean matrix with recursive splitting

Here is an attempt to avoid the quadratic time. If the argument is smaller than a certain size, we use the second method above (which is quadratic, but not so bad for smaller arguments).If the argument is larger than a certain size, we split it into two smaller parts, so that there are no titles shared between the two. Then the method is applied recursively to the parts.

By experimenting, the "certain size" appears to be about 256 on my computer.

third =: 4 : 0

if. 0 = # x do. return. 0 2 $ 3 end.

if. 0 = # y do. return. 0 2 $ 3 end.

'a t' =. |: x

'tt s' =. |: y

if. 256 > # x do.

bm =. t =/ tt NB. boolean matrix of matches

sm =. $. bm

im =. 4 $. sm NB. index-matrix

'i j' =. |: im

(i { a),. (j { s)

else.

p =: <. -: (>./t) + (<./t) NB. choose "pivot" title

pv =: t <: p

x1 =. pv # x

x2 =. (-. pv) # x

assert. (#x1) < (#x)

assert. (#x2) < (#x)

qv =. tt <: p

y1 =. qv # y

y2 =. (-. qv) # y

assert. (#y1) < (#y)

assert. (#y2) < (#y)

(x1 third y1) , (x2 third y2)

end.

)

Check correctness :

(AT2 third TS2) same (AT2 second TS2) 1And timings. Experiment on my computer shows the second method will run out of space where the third method will succeed.

'AT4 TS4' =: maketestdata 30000 'AT5 TS5' =: maketestdata 100000 t4a =: 6!:2 'AT4 second TS4' t5 =: 6!:2 'AT2 third TS2' t6 =: 6!:2 'AT3 third TS3' t7 =: 6!:2 'AT4 third TS4' t8 =: 6!:2 'AT5 third TS5' a =: ' '; (#AT2); (#AT3) ; (#AT4); (#AT5) b =: 'second'; t2; t4; t4a; 'limit error' c =: 'third' ; t5; t6; t7 ; t8 3 5 $a,b,c +------+----------+---------+---------+-----------+ | |1000 |10000 |30000 |100000 | +------+----------+---------+---------+-----------+ |second|0.00337303|0.321806 |3.05887 |limit error| +------+----------+---------+---------+-----------+ |third |0.00134601|0.0173196|0.0553821|0.192562 | +------+----------+---------+---------+-----------+In conclusion, the third method is clearly superior but considerably more complex.

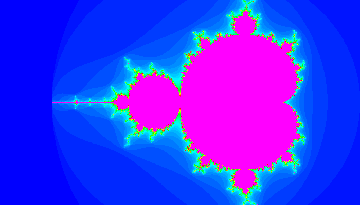

31.6 Golden Rule Example 4: Mandelbrot Set

The Mandelbrot Set is a fractal image needing much computation to produce. In writing the following, I have found to be helpful this Wikipedia article .

Computation of the image requires, for every pixel in the image, iteration of a single scalar function until a condition is satisfied. Different pixels will require different numbers of iterations. The final result is the array of counts of iterations for each pixel. Hence it may appear that the Mandelbrot Set is an inescapably scalar computation. It is not, as the following is meant to show. The Golden Rule applies.

31.6.1 Scalar Version

The construction of an image begins with choosing a grid of points on the complex plane, one for each pixel in the image. Here is a verb for conveniently constructing the grid.makegrid =: 4 : 0 'm n' =. x 'px py qx qy ' =. , +. y (|. py + (i.m) * ((qy-py) % m-1)) (j.~ /) (px + (i.n) * ((qx-px) % n-1)) )The left argument specifies the grid as m-by-n pixels. The right argument specifies the positions of lower-left and upper-right corners of the image as points in the complex plane.

To demonstrate with a tiny grid:

3 4 makegrid 0j0 3j4 0j4 1j4 2j4 3j4 0j2 1j2 2j2 3j2 0 1 2 3For a Mandelbrot image, this is more suitable:

GRID =: 400 700 makegrid _2.5j_1 1j1

Here, the right argument is chosen to be _2.5j_1 1j1

because it is known that the

whole of the Mandelbrot image is contained within this region of the complex plane.

Notice that this region is a rectangle with sides in the ration 4 : 7.

The left argument, m-by-n pixels, is chosen to be

in the same ratio.

The image is computed by applying a Mandelbrot function to each pixel in the grid. Here is a suitable Mandelbrot function. It follows the design outlined in the Wikipedia article,

mfn1 =: 3 : 0

NB. y is one pixel-position

v =. 0j0

n =. 0

while. (2 > | v) *. (n < MAXITER) do.

v =. y + *: v

n =. n+1

end.

n

)

We need to choose a value for MAXITER, the maximum number of iterations.

The higher the maximum, the more complex the resulting image.

For present purposes let us choose a maximum of 64 iterations,

which will give a recognisable image.

MAXITER =: 64 NB. maximum number of iterations image1 =: mfn1 " 0 GRIDThe result image1 is a matrix of integers, which can be mapped to colors and then displayed on-screen with:

require '~addons/graphics/viewmat/viewmat.ijs'

viewmat image1to produce an image looking something like this:

31.6.2 Planar Version

Now we look at a version which computes all pixels at once. Here is a first attempt. It is is a straightforward development of mfn1 but here all the computations for every pixel are allowed to run for the maximumum number of iterations.

mfn3 =: 3 : 0 NB. y is entire grid

N =. ($ y) $ 0

v =. 0j0

for_k. i. MAXITER-1 do.

v =. y + *: v

N =. N + (2 > | v)

end.

1 + N

)

For small values of MAXITER, this is OK.

A quick demonstration, firstly of correctness:

it produces the same result as mfn1.

MAXITER =: 9 (mfn1 " 0 GRID) -: (mfn3 " 2 GRID) 1And it's faster:

e3a =: 'mfn1 " 0 GRID NB. Wikip. with MAXITER=9' e3b =: 'mfn3 " 2 GRID NB. Planar with MAXITER=9' compare e3a;e3b +----------------------------------------+--------+ |mfn1 " 0 GRID NB. Wikip. with MAXITER=9|6.06934 | +----------------------------------------+--------+ |mfn3 " 2 GRID NB. Planar with MAXITER=9|0.168251| +----------------------------------------+--------+Unfortunately there is a problem with any larger values of MAXITER. The repeated squaring of the complex numbers in v will ultimately produce, not infinity, but a "NaN Error", caused by subtracting infinities. Observe:

(*: ^: 9) 1j3 NB. this is OK 1.96052e255j_9.80593e255 (*: ^: 30) 1j3 NB. but this is not |NaN error | (*:^:30)1j3 |[-589] c:\users\homer\X15\temp.ijsHere is an attempt to avoid the NaN errors. One cycle in every 8, those values in v which have "escaped", (that is, no longer contribute to the final result N) are reset to small values to prevent them increasing without limit.

mfn4 =: 3 : 0

N =. ($ y) $ 0

v =. 0j0

for_k. i. MAXITER - 1 do.

v =. y + *: v

N =. N + 2 > | v

if. 0 = 8 | k do.

e =. N < k

v =. e } v ,: 1.5j1.5

end.

end.

N+1

)

In spite of the burden of resetting,

the timing looks about 10 times faster than the scalar method:

MAXITER =: 64 e1 =: 'image1 =: mfn1 " 0 GRID NB. Scalar' e4 =: 'image4 =: mfn4 " 2 GRID NB. Planar, resetting' compare e1 ; e4 +---------------------------------------------+-------+ |image1 =: mfn1 " 0 GRID NB. Scalar |17.6847| +---------------------------------------------+-------+ |image4 =: mfn4 " 2 GRID NB. Planar, resetting|1.50849| +---------------------------------------------+-------+and we check the result is correct:

image4 -: image1 1

31.7 The Special Code of Appendix B of the Dictionary

In Appendix B of the J Dictionary there are listed about 80 different expressions which are given special treatment by the interpreter to improve performance. Many more expressions are listed in the Release NotesAn example is +/ . Notice that the speedup only occurs when +/ itself (as opposed to something equivalent) is recognised.

data =: ? 1e6 $ 1e6 NB. a million random integers plus =: + compare 'plus / data' ; '+/ data' +-----------+----------+ |plus / data|0.220362 | +-----------+----------+ |+/ data |0.00157533| +-----------+----------+The special expressions can be unmasked with the f. adverb which translates all defined names into the built-in functions.

foo =: plus / compare 'foo data'; 'foo f. data' +-----------+----------+ |foo data |0.221123 | +-----------+----------+ |foo f. data|0.00160007| +-----------+----------+The recommendation here is NOT that the programmer should look for opportunities to use these special cases. The recommendation is ONLY to allow the interpreter to find them, by giving, where appropriate, a final little polish to tacit definitions with f. .

This brings us to the end of Chapter 31